Information Architecture is both a familiar and foreign concept to me. As a web developer, I followed lots of tips on how to structure information in a way to make it more useful. Being the kind of person who likes both systems and structure, its principles appealed to me immediately. I’ve followed the work of Peter Morville and others for a long time and loved any ideas that encouraged deepening the overall structure of a site. I spent a long time working with various content management systems (and even developing my own) which reflected a strong hierarchy, but one that had multiple points of view (Never forget, everything is miscellaneous). But then something happened. I learned to relax and love the social side of the internet.

Information Architecture is both a familiar and foreign concept to me. As a web developer, I followed lots of tips on how to structure information in a way to make it more useful. Being the kind of person who likes both systems and structure, its principles appealed to me immediately. I’ve followed the work of Peter Morville and others for a long time and loved any ideas that encouraged deepening the overall structure of a site. I spent a long time working with various content management systems (and even developing my own) which reflected a strong hierarchy, but one that had multiple points of view (Never forget, everything is miscellaneous). But then something happened. I learned to relax and love the social side of the internet.

Where my thinking on Information Architecture changed was when I realized how the very same principles I was applying to structure information would also allow me (or enable others) to produce unstructured informal information. When I began to use WordPress as the main platform for most of my projects, I immediately gave up creating URLs that represented a hierarchy. This freeing moment was instigated because WordPress is a flat document system and because the categorization and tagging of posts does not need to fix any one post to a particular structure. In other words, you can constantly re-evaluate how you organize your information. So freeing!

But from there, I jumped to the idea that the actual production of your website, or more properly, your information could be so informal and so unstructured on the surface, because most of the traffic to your site comes from the sides, not through the homepage. Early IA focused a lot on deep structure, especially navigation menus. I remember being at an InfoCamp un-conference in Seattle in 2011 in a session in which the whole room was critizing Apple’s site for having terrible IA. Instead someone referenced one of IBM’s sites, because it clearly showed the hierarchy and enabled one to understand the site. I quickly disagreed (and almost got pounced upon) because I argued that it wasn’t what you saw, it was whether you could find what you needed. And simply put, I became overwhelmed by the IBM site.

This little story and the idea that website is dead (it’s an ecosystem of information, not a building) has taken me to even further lengths to de-emphasize site-wide top-level navigation. I find it is often badly designed and misleading. I like to reference Quartz’s site which uses a dynamic top-level navigation menu. This is the true way to think about IA now. We’re designing something deeper. There is no hierarchy. Good IA is about findability and usability.

Being able to find something these days has two main components (and probably more). The first is to be able use categorization, tags and dynamic, user-informed navigation to help someone viewing your content to find equally useful related content. One part of this is to acknowledge and accept that not everyone is interested in all that your organization does. You also need to acknowledge that you may not have suitable related content (at least yet). But if you do, you help the person along by providing some quick links. These can be manually created by hypertext (including external links). The biggest issue here is managing your links as your infrastructure changes. You’ll also need to build deep indexes for your data. This part is properly the most traditional part of IA.

The second component of findability is having good content. The two most interesting fields that impact this are content strategy and social media strategy. They help to produce meaningful useful content that travels well. I could and should write more about those. But for now, understand that if your information is produced well, it will be indexed properly and shared and the people interested in your information will find it. Keep in mind that you simply might have information that no one cares about. Although this is not likely true – the world is just too large now – but your expectations of engagement may be seriously overstated. I’m also describing a smaller site, one which generates most of its traffic from outside. There are obviously large businesses like Amazon, where people spend hours searching within. But even Amazon understands the power of social networks and recognizes that few algorithms can compete with your friends.

Now usability has already been somewhat addressed, since I’ve made the argument that only useful information gets found. So obviously your content strategy plays a big role in your infrastructure. But let’s take it one more step and outline an important aspect of usability, namely the user experience (UX). Now, UX, which is very different from user interface (UI) (note: see here my favourite example of their differences) provides a focal point for how people experience your information. If they struggle to understand it or to find related content within your infrastructure, you clearly have some IA issues. The ability to provide a meaningful experience of your information directly draws on how useful it is – if it is produced well, so that it can be found (indexed and shared) by those who are looking, once they find it, can they use it how they want to? This question may open up some larger issues around who needs to access your information and how (ie. OpenData and OpenGovernment).

This final point inevitably leads me all the way back to how WordPress and my experience of social networks began to change how I thought about IA. Because when it all comes down to it, if you can hand someone exactly want they want and nothing more, your information is useful. They don’t need to explore your website or get to know your business. They need something and once they found it, they are happy. Job well done. Good IA to the rescue. So what does this mean for how you structure your site. It really means that you learn how to produce your content in small manageable bits. Shareable fragments – single posts, with only the relevant information for the task at hand. I know that some would argue that this kind of piecemeal production will lead to duplications and difficulty in managing the information, but here is where I think we’ve already failed and we’re simply not prepared to acknowledge it. Here’s some case studies, or properly speaking, questions that will illustrate our existing issues:

- How many sites use language that expresses the future? At what point do you update the language?

- What kind of system does your organization use to audit past info? What is the cost of maintaining it? Is it worth it and advisable to remove old and inaccurate information?

The point of these two small illustrations is to suggest that now we are producing information at such a rate we can no longer worry about the past. Social networks have mentally prepared us for this. Deleting a tweet to correct spelling is seen by many people as a waste of time. Bloggers, if they need to fix an error, will either use strike-through to keep track of the change, or simply write a new post and let the dateline explain the addition. Both of these are examples of the influence of digital information at a time where there is too much and it travels too fast. They are important considerations that have changed the way we think about IA.

So, here we, producing fragments of useful information, never stopping to correct or fix the past, only moving forward, pushing out into the social networks. How is the Information Architect to think about their job now? Well, for me, it still comes back to the basic principles. We’re designing information so it can be found and is useful. It involves a lot of study (case-studies, projections, analysis) of who might want to use your information. It involves defining these people using techniques that Content Strategists discuss. It involves continuing to evaluate your content against these principles and then stepping back, watching who uses it and why and when, and then asking yourself the same question again: are the right people finding our content? Or, is our content useful to the right people?

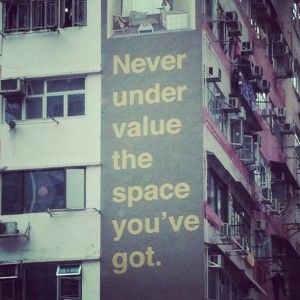

Information Architecture was originally coined by an architect, Saul Richard Wurman. He came up with the term to illustrate the problems of making information useful, specially, though in the context of space. Because Architecture, and perhaps better seen in Landscape Architecture or Urban Design, is all about connecting people to their space. And as the world grew and our physical spaces took on a new intense large presence in our everyday lives, and specifically one that we didn’t so easily control, it has become more important to think about how we produce space before we begin building it.

And so, to return to where I began, as an apologist and likely confusing information theorist, I would like to make a small point. I am an Information Architect who encourages people to build unstructured informal spaces, because it is through our continuous development that we begin to produce the kind of information that is truly useful. And overall, the structure we impose is not constructed from above or before we begin, it is structure that develops over time through the use of information.